About the University of Oxford

Oxford is a world-leading centre of learning, teaching and research and the oldest university in the English-speaking world.

History

Oxford is a unique and historic institution. As the oldest university in the English-speaking world, it can lay claim to nine centuries of continuous existence. Here’s a timeline of key dates:

Evidence of teaching

There is no clear date of foundation but teaching existed at Oxford in some form in 1096.

(Image credit: Shutterstock)

A Paris ban

Oxford developed rapidly from 1167, when Henry II banned English students from attending the University of Paris following a quarrel with Thomas Becket.

(Image: Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury stained glass window in the Chapter House at Westminster Abbey. Credit: Shutterstock.)

A notable visitor

In 1188, the historian Gerald of Wales gave a public reading to the assembled Oxford dons (university lecturers, especially at Oxford or Cambridge). As a royal clerk to the king and two archbishops, Gerald of Wales travelled widely and wrote extensively.

(Image credit: Shutterstock)

First overseas student

In around 1190 the arrival of Emo of Friesland, the first known overseas student, set in motion the University’s tradition of developing international scholarly links.

(Image credit: Shutterstock)

The title of Chancellor

By 1201 the University was headed by a ‘magister scholarum (head of an ecclesiastical school) Oxonie’, on whom the title of Chancellor was later conferred in 1214, and in 1231 the Masters were recognised as a universitas or corporation.

(Image: The current Chancellor, Lord Patten of Barnes.)

First colleges

During the 13th century, rioting between town and gown (townspeople and students) hastened the establishment of primitive halls of residence.

These were succeeded by the first of Oxford’s colleges, which began as endowed houses or medieval halls of residence, under the supervision of a Master.

Established between 1249 and 1264, University, Balliol and Merton Colleges are the oldest.

(Image: Merton College and chapel, from the first quadrangle, 1775-1827. Credit: Oxford University Images / Oxfordshire History Centre)

Tributes from kings

Less than a century later, Oxford had achieved eminence above every other seat of learning, and won the praises of popes, kings and sages by virtue of its antiquity, curriculum, doctrine and privileges. In 1355, Edward III paid tribute to the University for its invaluable contribution to learning. He also commented on the services rendered to the state by distinguished Oxford graduates.

(Image credit: Shutterstock)

Religious and political controversy

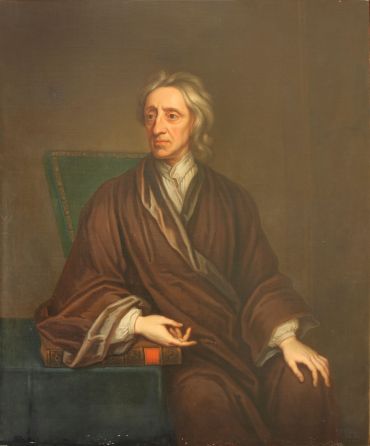

John Locke (1632-1704) by Thomas Gibson. Image: Oxford University Images / Bodleian Library

Early on, Oxford became a centre for lively controversy with scholars involved in religious and political disputes.

John Wyclif, a 14th-century Master of Balliol, campaigned for a Bible in English, against the wishes of the papacy.

In the 16th century, Henry VIII forced the University to accept his divorce from Catherine of Aragon, and the Anglican churchmen Cranmer, Latimer and Ridley were later tried for heresy and burnt at the stake in the city.

The University was Royalist during the Civil War and Charles I held a counter-Parliament in the University’s Convocation House.

In the late 17th century, the Oxford philosopher John Locke, suspected of treason, was forced to flee the country.

Scientific discovery and religious revival

Edmond Halley, astronomer (1656-1742), by Thomas Murray. OUImages / Bodleian Library

The 18th century became an era of scientific discovery and religious revival.

Edmond Halley, Professor of Geometry, predicted the return of the comet that bears his name.

John and Charles Wesley’s prayer meetings laid the foundations for the Methodist Society.

Find out more:

British Prime Ministers | University of Oxford

Award winners | University of Oxford

The Oxford Movement

From 1833 onwards, the Oxford Movement sought to revitalise the Catholic aspects of the Anglican Church. One of its leaders, John Henry Newman, became a Roman Catholic in 1845 and was later made a Cardinal. In 2019 he was canonised as a saint.

(Image: Close-up of Cardinal Newman bust from Trinity College Garden Quad, Oxford University. Credit: Shutterstock.)

A famous debate

In 1860 the new University Museum was the scene of a famous debate between Thomas Huxley, champion of evolution, and Bishop Wilberforce.

Women become members

From 1878 academic halls were established for women, who were admitted as full members of the University from 1920. By 1986, all of Oxford’s male colleges had changed their statutes to admit women and, since 2008, all colleges have admitted men and women.

(Image: The first women to be awarded degrees at Oxford University. Credit: Lady Margaret Hall.)

Major research capabilities

During the 20th and early 21st centuries, Oxford established major new research capacities in the natural and applied sciences, including medicine. In so doing, it has enhanced and strengthened its traditional role as an international focus for learning and a forum for intellectual debate.

A life-saving vaccine

Oxford University has been at the centre of the COVID-19 response from the very onset of the crisis, remaining at the forefront of global efforts to combat the disease and to mitigate its many effects, such as developing a vaccine and identifying treatments. By early 2022, more than 2.6 billion doses of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine had been supplied to over 180 countries, with approximately two-thirds going to low and middle-income countries. The vaccine is estimated to have helped prevent 50 million COVID-19 cases, five million hospitalisations, and saved more than one million lives.

Divisions and Departments

There are four academic divisions within Oxford University. All have a full-time divisional head and an elected divisional board. Also listed are the Department for Continuing Education, and the University’s Gardens, Libraries and Museums.

Humanities Division

American Institute, Rothermere

Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies

Faculty of English Language and Literature

Faculty of Linguistics, Philology & Phonetics

Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages

Faculty of Theology and Religion

The Oxford Research Centre in the Humanities (TORCH)

Mathematical, Physical & Life Sciences Division

Department of (formerly Zoology and Plant Sciences), Biology

Department of Computer Science

Department of Engineering Science

Medical Sciences Division

Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine

Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences

Department of Experimental Psychology

Radcliffe Department of Medicine

Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences

Sir William Dunn School of Pathology

Department of Physiology, Anatomy & Genetics

Nuffield Department of Population Health

Department of Primary Care Health Sciences

Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences

Nuffield Department of Women’s & Reproductive Health

Social Sciences Division

School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography

School of Geography and the Environment

Oxford School of Global and Area Studies

Blavatnik School of Government

Department of International Development

Department of Politics and International Relations

Department of Social Policy and Intervention

Department for Continuing Education

Gardens, Libraries and Museums

Facts and figures

Did you know?

Oxford was ranked first in the world in the Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings for 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024 and 2025 – a record nine consecutive years.

There are more than 26,000 students at Oxford, including 12,470 undergraduates and 13,920 postgraduates.

Entry to undergraduate courses at Oxford continues to be very competitive: there are usually only around 3,300 places, and over 23,000 people applied to start in 2023.

The majority of Oxford’s UK undergraduates come from state schools. Over 67% of UK students admitted in 2023 were from the state sector.

450 postgraduate courses received applications for year of entry 2022/23 (including part-time variants).

For 2022/23 entry, over 37,500 applications were received for some 6,056 postgraduate places.

International students make up 46% of our total student body – around 12,075 students. Students come to Oxford from more than 160 countries and territories (as of 1 December 2022)

According to the 2021 Research Excellence Framework, which assesses the quality of research in UK Higher Education Institutions, Oxford’s submission had the highest volume of world-leading research¹.

The University of Oxford contributes around £15.7 billion to the UK economy, and supports more than 28,000 full time jobs (2018/19). Find out more here.

(¹Largest volume of world-leading research is calculated from the sum of (overall %4* x submitted FTE) across all submissions.)

Governance

Oxford’s distinctive governance structure stems from its long history.

Congregation is the sovereign body of the University and acts as its ‘parliament’. It has just over 5,000 members, including academic staff; heads and other members of governing bodies of colleges; and senior research, computing, library and administrative staff. Congregation has responsibility for:

Approving changes to the University’s statutes and regulations;

Considering major policy issues submitted by Council or members of Congregation;

Electing members to Council and other University bodies, and approving the appointment of the Vice-Chancellor.

Council is the University’s principal executive and policy-making body. It has 26 members, including four from outside the University. It is responsible for the academic policy and strategic direction of the University, for its administration, and for the management of its finances and property. It has five major committees: Education Committee, General Purposes Committee, Personnel Committee, Planning and Resource Allocation Committee, and Research Committee.

Colleges

The 39 colleges, though independent and self-governing, form a core element of the University, to which they are related in a federal system. Each college is granted a charter approved by the Privy Council, under which it is governed by a Head of House and a Governing Body comprising of a number of Fellows, most of whom also hold University posts. There are also four Permanent Private Halls, which were founded by different Christian denominations, and still retain their religious character today. The Conference of Colleges represents the common concerns of the colleges on Council, its committees, and the four Divisional Boards, and acts as a body for intercollegiate discussion and decision-making.

Divisions and departments

The University’s academic departments, faculties and research centres are grouped into four divisions: Humanities; Mathematical, Physical and Life Sciences; Medical Sciences; and Social Sciences. Day-to-day decision-making in matters such as finance and planning is devolved to the divisions. The Department for Continuing Education is the responsibility of a separate board.

The Chancellor, who is usually an eminent public figure elected for life, serves as the titular head of the University, presiding over all major ceremonies.

The Vice-Chancellor holds office for seven years and is the senior officer of the University.

There are six Pro-Vice-Chancellors who have specific portfolios in Development and External Affairs; Education; Innovation; People & Digital; Planning and Resources; and Research. There are also up to ten Pro-Vice-Chancellors without portfolio, who undertake a range of duties on behalf of the Vice-Chancellor, including presiding at degree ceremonies and chairing electoral boards.

Further information about University governance on the Planning and Council Secretariat website

Information on and links to the main bodies involved in the University’s governance, its legislation, its elections, and on the team supporting the governance structures.